Editor’s note: this interview was originally published on April 4 2022, when Facing Monsters was being premiered around Australia. It seemed fitting to revisit again since finding a new home on Stab Premium.

On Thursday the 9th of June, 2020, as the globe tilted off-axis in a blur of Covid and Trump and Black Life-related matters, noted West Australian charger Kerby Brown went missing.

You mightn’t have seen any notices for the hirsute heathen who lived his life on a knife’s edge, walking a tightrope between kamikaze acts at sea and self-destructive ones on land, but the day Kerby shut down his social media was the day one of surfing’s most visible hellmen ceased to exist in the minds of the audience who built his career.

“It’s funny the way the world is these days,” says Kerby, as I hit record, sitting on his verandah in Denmark, WA. “People assume if you’re not posting then you’re not doing anything, you’re not living. But it’s quite the opposite really…”

For Kerby, the opposite meant making his magnum opus, Facing Monsters, a cinematic deep dive into an extraordinary surfing life, the bulk of which was filmed in gloriously high definition sometime after his zero-dark-thirty moment in the Australian winter of 2020. “To go offline was so refreshing,” says Kerby. “I get so much out of doing something and not really telling anyone. When we’re filming I always prefer to sit on stuff and collect quality, rather than put it out straight away to get that instant gratification; that doesn’t interest me at all. With this project we decided early on that if we were going to do something we were going to do it properly, and it would have some purpose. I think we’ve achieved that.”

As Facing Monsters lays out in wonky low-definition handy cam footage, Kerby and his younger brother Cortney grew up in Kalbarri, on Western Australia’s mid-west coast. A tourist town that hates tourists, Kalbarri boasts a couple of world class lefts, but good luck paddling out and swinging into a set. Quiksilver Young Gun Ry Craike developed his trademark fin waft over years of practice at the best wave in town, while Clay Marzo even moved in for a few years to surf his brains out in the middle of nowhere. While these days we know Kerby as a slab hunting lunatic, the early scenes in the movie showcase an effortless style groomed in high-performance conditions, which then meshes perfectly with the heaving desert drainers even further to the state’s north.

“I surfed with Kerb all the time growing up,” says West Aussie overlord Taj Burrow. “I used to love meeting up whenever he came down my way or if I went to Kalbarri. I think everyone forgets how sick his style is in regular waves too — like, how good does he look at the point up there? He fucken rips!”

Like most promising Aussie juniors, Kerb took his talents to the World Qualifying Series, though the shitty waves held little appeal compared to the bright lights of whichever seaside town was having its annual surfing festival that weekend. Kerby’s world tour dreams faded fast. “I just remember Kerby being super angry on the QS,” says Taj, “So to be honest, it’s good that he gave it away. He’s much more suited to the wild anyway.”

“He’s better suited to the wild,” says Taj Burrow. That checks out.

“He’s better suited to the wild,” says Taj Burrow. That checks out.

Kerby soon found himself back in Perth chasing the woman he loved, Nicole Jardine, while doing all he could to scare her off thanks to the West Australian capital’s lack of surf and the debaucherous behaviour it leads to. These scenes are also covered in low-def, this time of the post-midnight smart phone variety, and give you a scary insight into the demons Kerb was battling on dry land.

Something had to give, and when Nicole announced that she was pregnant Kerby realised that pulling his head in was overdue. Shortly after the birth of son his Phoenix, he started working fly-in fly-out on supply vessels in the north-west oil fields, while moving the family to the deep south of WA to be, as Cortney says, “closer to the monsters.”

“I always wanted to live life to the fullest and be right there in the moment,” Kerby told me in a 2017 interview for Surfing Life. “A few years back I was paid just enough by sponsors to get by. I was partying way too much and was off the rails at that point, waiting for big swells, not really surfing much in-between them, and drinking a lot, doing really stupid shit. Then all of a sudden I had a kid on the way…”

Responsibility for an infant’s welfare, a pay cheque, and proximity to the world’s most dangerous waves might just have saved Kerby Brown’s life.

Kerbs, presumably showing his kids where the monsters live.

Kerbs, presumably showing his kids where the monsters live.

“Having a baby forced me to get my shit together. I realised I had to look for a job so I could provide for my family. I was lucky; I had friends in oil and gas working offshore on boats. The industry was booming and with a little help from the right people I did some training and fell straight into a pretty good offshore gig.”

“When my son was just 12-days-old I got flown up for my first job, working five weeks on, five weeks off. I was getting paid north of 100K (AUD) and still had six months off every year to chase waves. Even though I was leaving my loved ones behind for long stretches this seemed like the best option. I was making good money, providing for my family, and the bonus was I could also now afford to throw myself into whatever waves I wanted when I was home.”

“There is big wave surfing,” says next James Bond and A-list waterman Kai Lenny, “and then there is what Kerby Brown and his mates are doing on the edge of the earth in Western Australia. I hope I can join them one day.” There is a delicious irony to be found in a man from Maui, home of Jaws, wanting to one day whip in with Kerby and co. down under. But while the outer reefs of Pe’ahi may have led to the invention of tow surfing in the dying days of the last millennium, the shallow water slabs of Australia’s deep south took that game to a whole new level in the 21st century. For Kerby and his ratbag mates the timing couldn’t have been better.

If you hurt yourself here, you will be staying hurt for quite some time.

If you hurt yourself here, you will be staying hurt for quite some time.

“There are these waves that you can’t normally surf,” says Kerby, “then you throw a jet ski in the mix and that makes it possible, and opens up a whole new world.”

“I couldn’t get enough of shooting surfers like Kerby,” says Margaret River photographer Russell Ord, in that same Surfing Life article. “I was all about guys who had dedicated their lives to their art, were well respected at their local break for paddling into bombs, and had slowly and surely worked their way up to waves like The Right.”

A desirable wave, in the minds of a select few.

A desirable wave, in the minds of a select few.

“Kerby was the leader of the pack in that regard. He had true surfing talent, combined with so many years of experience. If you didn’t know better it would be easy just to write off his willingness to go hard as crazy, he was that good. But there’s no way in hell you’re letting go of the rope as deep as he does on his backhand unless you’re on top of your game.”

“Kerby is just one of those guys who has no limits,” occasional sparring partner Jack Robinson puts it, slightly more succinctly.

Ten years ago Kerby couldn’t let go of a towrope without turning up in a video part or landing a magazine cover, and the decade since then has been a healthy mixture of working, surfing, and general family man duties in sleepy, small town Denmark. Then the mainstream came knocking, and in early March, 2022, Facing Monsters will finally be projected onto Australian silver screens, after Covid saw cinemas sit fallow across the country for the best part of the last two years, and hampered efforts to release the film earlier.

The Facing Monsters premiere packed mainstream cinemas all over Australia.

The Facing Monsters premiere packed mainstream cinemas all over Australia.

Ironically, Covid also played a small part in helping the project come to life. “With all the craziness it was almost impossible to get a crew together in the one location where it was safe to film anything,” says Kerby’s partner Nicole Jardine. “But we happened to have a really small, agile team that was able to make it happen. With Western Australia’s borders locked and us not having any Covid cases, we were free to roam.”

Facing Monsters is Kerby’s life story, told in concert with the short filming window that led to the movie’s insane crescendo. Spoiler alert: it’s not pretty. Thankfully Kerby’s great mate and Facing Monsters director of photography Rick Rifici managed to keep the camera rolling, and some of the scenes he captures, both on land and in the ocean, will have you scratching your head in disbelief.

“Rick is the main guy behind the movie,” say Kerby. “His work is amazing. I’ve filmed with Rick forever, and always thought it was a shame just to put his work straight up on the internet. As challenging as it was for me, if I was going to throw myself into a project I wanted it to have a bit of meaning to it.”

Kerby is no stranger to getting deep.

Kerby is no stranger to getting deep.

“It was a fly on the wall approach,” says Kerby when I ask him what the plan of attack was. “For those few months of filming we wanted to capture things as they happened. We wanted to keep it raw and honest, and just follow along with whatever unfolded. The production team definitely questioned where everything was heading, and all we could really say was that naturally, drama would unfold. Chasing these sorts of waves something will always go down, usually good and bad, and we were sure that if we kept chasing swells there would be plenty of drama. We were cut short, but in the end that gave the film even more meaning and depth.”

It’s hard to talk about the film without giving too much away, but it’s as much a love story between Kerby and Nicole as it is a surf movie. It’s the tale of Kerby risking his life to stay sane, but doing so knowing he has kids to come home to. It’s the trials and tribulations of low-key star-of-the-show Cortney as the tortured little brother who tows his best mate into waves he knows could kill him, yet who would prefer he was responsible before anyone else.“ Kerby would do it without me anyway,” grimaces Cortney, his Hollywood jawline failing to dampen the tremble in his voice.

Nicole is the yin to Kerby’s yang.

Nicole is the yin to Kerby’s yang.

The West Australian landscape plays a starring role, and is a constant reminder of the wild outdoors – from the red dirt and emerald Indian Ocean of the Mid-West to the granite outcrops and black Southern Ocean swells of the Great Southern – that have shaped the life of the shy man who hides behind a bushranger’s beard.

Then there’s Glenn Brown—lifelong crayfisherman, surfer and musician turned father to two surfing studs. A reserved character he grimaces watching the pair surf deathly-looking reefs. “This is like asking me to go to his funeral,” says Glenn, as Kerby tows into another below sea level beast. The guy who pushed his kids into their first waves remains fiercely proud at all times and knows he can’t begrudge their passion, no matter how dangerous it seems all these years later. He’s got all the boys’ magazine covers on his wall, and soothes his nerves plucking away at his guitar in scenes that eventually make the movie. “I’ve grown up listening to him play,” says Kerby, “so to have his music and vocals and guitar layered through the film was really cool, and makes it that little bit more special.” Is Glenn thrilled to be on a soundtrack alongside Radiohead, I ask? “I really don’t think he’s that bothered,” Kerby laughs. “Says he’s not that much of a fan.”

Cortney and Kerby, cut from the same cloth.

Cortney and Kerby, cut from the same cloth.

Kerby is a reluctant study, ironically uncomfortable on camera for a character who stares danger down daily. “Doing a movie wasn’t a decision we made lightly,” says Kerby. “It was a big move for us to get out of the comfort zone, and especially for me to try and open up. We’re pretty private people and were skeptical about putting the kids out there too, amongst other things. The whole process has been a crazy journey, a real rollercoaster. From start to finish it was challenging, even just getting the first call saying it was going ahead was pretty daunting.”

To say Kerby rides the rollercoaster across the span of the movie is an understatement, but for all the various trauma he’s subjected to, Facing Monsters is a heartwarming tale. Surfer or not, there are lessons and inspiration aplenty for viewers from all walks.

“It’s hard to make surfing appeal to a broad audience and get people to appreciate what it is we do,” says Kerby. “If it’s just a surf film sometimes it’s hard to reach people who don’t surf, but so far so many non-surfers are loving the movie, really enjoying it and liking the story, which is great. The feedback has been really positive. It’s a genuine human story, about family and friendships, and people can relate to the relationships. They’re impressed by the surfing and the waves, but on the whole it’s the story that’s shining through the most.”

He’s strangely comfortable here.

He’s strangely comfortable here.

Mental health, and the various ways it can fail us or lift us up, are recurring themes in the movie. Kerby refused to shy away from being open on that front when filming. “Talking about my struggles was important,” he says. “I had to be honest so that people who’ve gone through hard times can relate and take a positive message out of the film. I’ve taken that self-destructive path for many years y’know; alcohol, drug abuse, for a long period of time. I was lucky to have surfing, and to have that passion inside me to pull me through in the end.

“The ocean pretty much saved me. By opening up and telling that side of my story, I hope that anyone who struggles with any of that kind of thing can see that there’s always light at the end of the tunnel, there’s always a way out. It doesn’t have to be the ocean, just follow anything you’re passionate about, anything in nature. Just get off the couch, there’s a lot of beauty out there.”

So far the movie has played a string of advanced screenings and film festivals, and all have met with rave reviews. “It’s crazy!” says Jack Robinson. “It’s a really good look into how Kerby goes about surfing the craziest waves you’ve ever seen.”

For Kerby though, the flipside of the film is far more important. “I’ve had heaps of messages since the first few screenings, thanking me for being honest. People telling me they’ve been dealing with their own shit and how it was cool to see someone else going through it, and to see where I’m at now.”

Now that the film is out, what’s Kerby going to do? More of this.

Now that the film is out, what’s Kerby going to do? More of this.

“It’s so refreshing to see someone be so open about their struggles,“ says 2017 world adaptive surfing champion Barney Miller, himself no stranger to overcoming huge adversity in life. “It’s inspiring to see the work Kerby put in on himself to beat his challenges and achieve success in the end. The movie is incredible!”

“To have people say they’ve been inspired and to thank me, that’s already made it all worthwhile,” says Kerby. “We didn’t do the film for money or fame or any of that, we did it for this one pure reason, to hopefully spread a good message and inspire people on any level, so to hear that kinda feedback from strangers is awesome. Feels like we’ve done our job.”

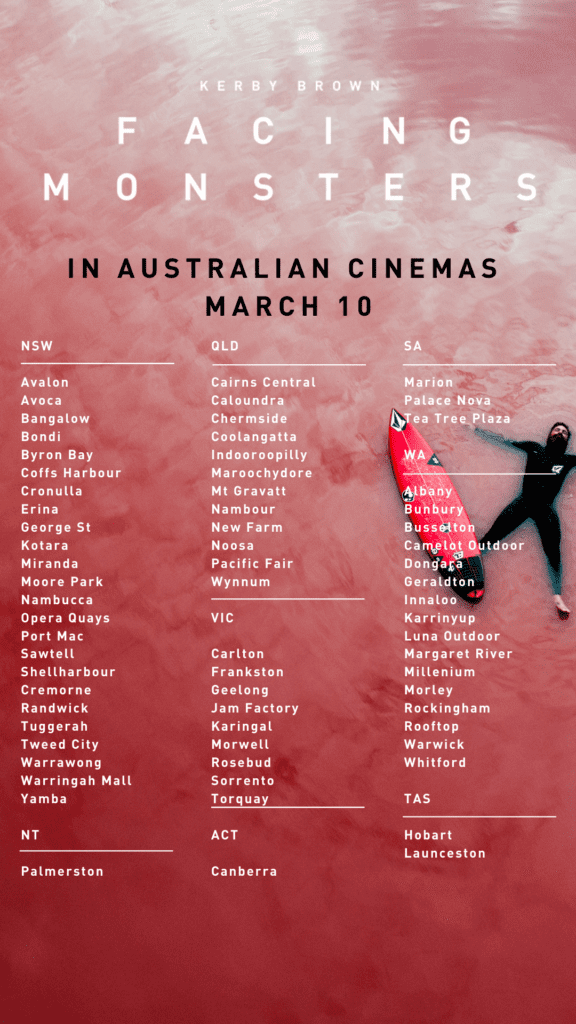

If you’d like to confirm that Kerby and his crew have indeed done their job then Facing Monsters begins a run of nationwide cinema screenings around Australia from today, March 10. We can’t encourage you strongly enough to get along to your local megaplex to support an incredible surfing movie, that is as hardcore and honest and mindblowing as they come, finally making its way onto the big screen. The experience is worth it for the insane cinematic surround sound of the breaking waves alone, but surely the film goes well with ice cream and popcorn too. Enjoy.

You can buy tix here

Q&A TOUR DATES:

- 9 Mar GOLD COAST

- 10 Mar NOOSA

- 12 Mar BRISBANE

- 15 Mar HOBART

- 17 Mar MELBOURNE

- 19 Mar ADELAIDE

- 20 Mar AVOCA BEACH

- 21 Mar HAYDEN ORPHEUM

- 22 Mar RANDWICK RITZ

- 24 Mar SAWTELL